Botany of Peyote

Edward F. Anderson

Chapter 8, Peyote, The Divine Cactus, ©1980 The Arizona Board of Regents

Published by The University of Arizona Press ISBN 0-8165-0680-9

Until the 1950s there had been no careful and extensive botanical studies of peyote. Plants which were brought into the chemist's laboratory—or the horticulturist's greenhouse—had little or no documentation, available only at the site of collection, about the place of origin or other important characteristics. As a result, plants from the same population were sometimes given different scientific names and those of separate regions often were given the same name. This absence of botanical understanding, primarily due to insufficient field and laboratory studies, consequently resulted in mistakes and confusion by historians, anthropologists, chemists, pharmacologists, and others. For example, numerous references have been made to peyote as belonging to the genus Anhalonium. This name is botanically invalid, as it was applied to the group of plants which had earlier been named Ariocarpus; hence, the later name Anhalonium cannot be used for that group or any other group of plants such as peyote. However, the name Anhalonium had been employed so widely for about a century that few people other than botanists specializing in taxonomy were aware of the fact that the name should not have been used. The confusion and difficulties that have resulted probably can never be completely straightened out.

Another serious problem was created in the 1890s when the German chemist Arthur Heffter received a shipment of poorly documented and incorrectly identified peyote specimens for laboratory analysis. These plants were to be the basis of some of the most important—and confusing—pioneer chemical studies of peyote. Heffter discovered that the plants he had received belonged to two distinct groups based on the alkaloids present but he claimed that he was unable to distinguish the groups on structural or morphological grounds. Since he had no collection and field data he decided that peyote simply consisted of two chemical forms. Jan G. Bruhn of the University of Uppsala and Bo Holmstedt of the Swedish Medical Research Council have thoroughly researched the literature dealing with this period of peyote history; their conclusion is that Heffter's batch of plants actually consisted of the two distinct species of peyote, which do have definite alkaloid differences.[1] A better botanical understanding of the group, as well as proper scientific data, would have prevented the introduction of much confusing information into the literature that has persisted for more than seventy-five years.

This frustrating botanical chaos concerning peyote existed for so long that in the 1950s a research biochemist interested in the hallucinogenic properties of the plant personally financed a graduate school program to study and determine the botanical relationships of the group and to unscramble the nomenclature. The botanical aspects are now much clearer.

The peyote cactus is a flowering plant of the family Cactaceae, which is a group of fleshy, spiny plants found primarily in the dry regions of the New World. Some of the characteristics which one normally sees in cacti are not readily evident in peyote, except for the obvious one of succulence. Spines, for example, are present only in very young seedlings. However, the cactus areole—the area on the stem that usually produces flowers and spines—is well pronounced in peyote and is identified by a tuft of hairs or trichomes. Flowers arise from within the center of the plant and, like other cacti, the perianth of peyote flowers is not sharply divided into sepals and petals; instead there is a transition from small, scale-like, outer perianth parts to large, colored, petal-like, inner ones. Another characteristic which shows that peyote belongs in the cactus family is the absence of visible leaves in either juvenile or mature plants. Leaves are greatly reduced and only microscopic in size; even the seed leaves or cotyledons are almost invisible in young seedlings because they are rounded, united, and quite small. Also, the vascular system of peyote is like that of other succulent cacti in which the secondary xylem is very simple and has only helical wall thickening.

BOTANICAL HISTORY

|

| Fig. 8.1 — The first illustration of peyote appeared in Curtis's Botanical Magazine in 1847 (plate 4296). |

Peyote was first described by western man in 1560 but it was not

until the nineteenth century that any plants reached the Old World

for scientific study. Apparently the French botanist Charles Lemaire

was the first person to publish a botanical name for peyote, but

unfortunately the name that Lemaire used for the plant, Echinocactus

williamsii, appeared in the year 1845 without description

and only in a horticultural catalog. Therefore, it was necessary

for Prince Salm-Dyck, another European botanist, to provide the

necessary description to botanically validate Lemaire's binomial.

No illustration accompanied either the Lemaire name or the description

by Salm-Dyck and it was not until 1847 that the first picture

of peyote appeared in Curtis' Botanical Magazine (figure

8.1).[2]

In the second half of the nineteenth century the characteristics

and scope of the large genus Echinocactus were disputed

by several European and American botanists; gradually its limits

were narrowed and new genera were proposed to contain species

that had once been included in it. In 1886, Theodore Rumpler proposed

that peyote be removed from Echinocactus and placed in

the new segregate genus Anhalonium, thus making the binomial

A. williamsii, a name which soon became widely used throughout

Europe and the U.S.3 Much earlier (1839) Lemaire had proposed

the name Anhalonium for another group of spineless cacti,

now correctly classified as Ariocarpus.[4] Anhalonium must

be considered as a later homonym for Ariocarpus, so, according

to the International Rules of Botanical Nomenclature, it cannot

be validly used as a generic name for any plant.[5] Ariocarpus

superficially resembles peyote, but clearly is a different genus.

In 1887, Dr. Louis Lewin, a German pharmacologist, received some

dried peyote labeled "Muscale Button" from the U.S.

firm of Parke, Davis and Company in Detroit, which had obtained

the material from Dr. John R. Briggs of Dallas, Texas, earlier

that year.[6] Lewin used some of this plant material in chemical

studies and found numerous new alkaloids; he also boiled some

of the dried "buttons" in water to restore something

of their living appearance and gave them to a German botanist,

Paul E. Hennings of the Royal Botanical Museum in Berlin for study.

Hennings noted that Lewin's plant material appeared similar to

the plant called "Anhalonium" williamsii (Echinocactus

williamsii Lemaire ex Salm-Dyck) but apparently differed somewhat

in the form of its vegetative body, namely in the characteristic

wool-filled center of the plant. Hennings decided that the dried

plant material given to him by Lewin was that of a new species,

which he formally named Anhalonium lewinii, in honor of

his colleague. His description was accompanied by two drawings,

one of the new species, A. lewinii, and the other of the

older species, A. williamsii.[7] The illustration of A.

lewinii shows a high mound of wool in the center of the plant.

Apparently, the drawing, which had been made from the dried plant

material that Lewin had boiled in water, was an incorrect reconstruction

of what had been the original appearance of the plant. When the

top of a peyote dries, the soft fleshy tissue is reduced greatly

in volume, whereas the wool does not decrease in size at all.

Therefore, the proportion of wool to what formerly was the fleshy

or vegetative part is greatly increased in the dried button. This

phenomenon presumably caused Hennings and Lewin to believe that

they had a new species of peyote when in actuality the plant material

they had studied was that of "Anhalonium" williamsii.[8]

Bruhn and Holmstedt have concluded that Lewin's plant material

known as "Anhalonium" williamsii was in fact

the southern species of peyote, Lophophora diffusa. The

specimens which Hennings described as the new species "Anhalonium"

lewinii belong to the northern species of peyote, L. williamsii.[9]

Additional confusion concerning the botanical classification of

peyote occurred in 1891 when the American botanist John Coulter

transferred peyote to Mammillaria, a genus commonly called

the pincushion or nipple cactuses Then, in 1894, a European named

S. Voss confused things even more by placing peyote in Ariocarpus,

the valid name for a distinct—and quite different—group of

plants that had been called Anhalonium also.[11] Finally,

in the same year Coulter proposed a new genus for peyote alone:

Lophophora.[12] This helped clarify the nomenclatural situation

because peyote had been included in at least five different genera

of cacti by the end of the nineteenth century. The group of plants

commonly called and used as peyote is unique within the cactus

family and deserves separation as the distinct genus Lophophora.

Beginning about 1900 numerous forms and variants of peyote were

collected in the field and sent to cactus collectors and horticulturists

in Europe and the United States. The highly variable peyote plants,

not seen as part of natural populations but as individual specimens

in pots, were often described as new and different species. None

of the taxonomic studies, however, were based on careful field

work, so little was known of the nature and range of variations

within naturally occurring peyote populations. By mid-century

greater accessibility of peyote locations in Texas and Mexico

permitted extensive field work which has shown that plants of

the genus Lophophora, especially in the north and central

regions of its distribution, are highly variable with regard to

vegetative characters (i.e. color, rib number, size, etc.). The

number and prominence of ribs, slight variations in color, and

the condition of trichomes or hairs have tended to be three of

the main characters which have delineated many of the proposed

species and varieties of peyote; however, these characters vary

so greatly even within single populations that they are an insufficient

basis for separating species—if a species is considered to be

a genetically distinct, self-reproducing natural population.

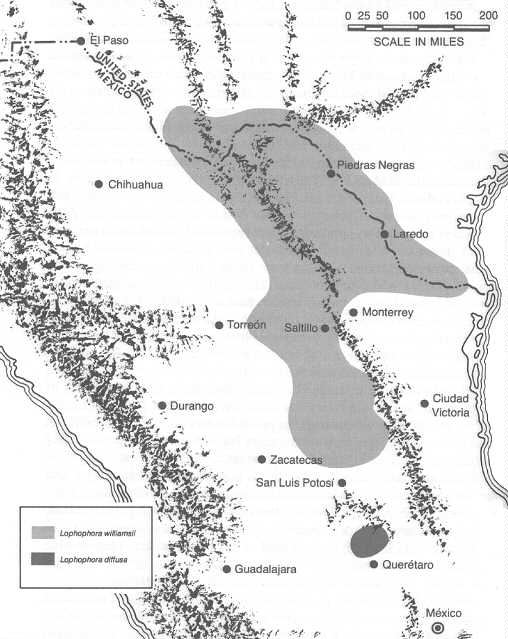

Field and laboratory studies show that there are two major and

distinct populations of peyote which represent two species:

(figure

8.2).[13] The first, Lophophora williamsii,

the commonly-known peyote cactus, comprises a large northern population

extending from southern Texas southward along the high plateau land of

northern Mexico. This variable and extensive population reaches its southern

limit in the Mexican state of San Luis Potosi where, near the

junction of federal highways 57 and 80, for example, it forms

large, variable clumps. The second species, L. diffusa,

is a more southern population that occurs in the dry central area

of the state of Queretaro, Mexico. This species differs from the

better-known L. williamsii by being yellowish-green rather

than blue-green in color, by lacking any type of ribs or furrows,

by having poorly developed podaria (elevated humps), and by being

a softer, more succulent plant.

COMMON NAMES OF LOPHOPHORA

The study of peyote has frequently been confused because the plant has received so many different common names. Fr. Bernardino de Sahagun first described the plant in 1560 when he referred to the use of the root "peiotl" by the Chichimeca Indians of Mexico.[14] The two most commonly used names, "peyote" and "peyotl," are modifications of that ancient word.The actual source and meaning of the word "peiotl" is disputed and at least three theories have been proposed to explain its etymology. Several Europeans have suggested that the term "peyote" came from the Aztec word "pepeyoni" or "pepeyon," which means "to excite."[15] A derived word from this is "peyona-nic," meaning "to stimulate or activate."

A similar proposal was made by V. A. Reko and extensively discussed by Richard Evans Schultes; they suggested that the term "peyote" came from the different Aztec word "pi-youtli," meaning "a small plant with narcotic action.''[16] This somewhat narrow interpretation of the kind of action should perhaps be broadened to mean "medicinal" rather than "narcotic," as the Indians certainly would have thought of the actions of the plant in the former context.

Probably the most widely accepted etymological explanation for the origin of the term "peyote" was suggested by A. de Molina, who claimed that it comes from the Náhuatl word "peyutl," which means, in his words: "capullo de seda, o de gusano."[17] This, translated from Spanish, means "silk cocoon or caterpillar's cocoon." Molina's explanation, therefore, proposed that the original word was applied to the plant because of its appearance rather than its physiological action. Certainly one of the most distinctive characteristics of peyote is the numerous tufts of white wool or hair. Dried plant material has an even greater proportion of the "silky material" and most of it must be plucked prior to eating. The presence of these woolly hairs seems to be of significance because some other pubescent (hairy or woolly) plants, not even cacti, have occasionally been called peyote by Mexicans. Examples of such non-cacti are Cotyledon caespitosa of the family Crassulaceae and Cacalia cordifolia and Senecio hartwegii of the family Compositae. These plants have little in common with the peyote cactus except for their pubescence and the fact that sometimes they have been used medicinally.

The Mexican word "piule," which is generally translated to mean "hallucinogenic plant," may have come indirectly from the word "peyote." R. Gordon Wasson, who has studied many hallucinogenic plants and fungi, suggested that "peyotl" or "peyutl" became "peyule," which was further corrupted into ''piule.''[18] "Piule" is also applied to Rivea corymbosa (Convolvulaceae).

Other names which are apparently variations in spelling (and pronunciation) of the basic word "peyote" or "peyotl" include: "pejote," "pellote," "peote," "Peyori," "peyot," "pezote," and "piotl." The many tribes of Indians who use peyote also have words for the plant in their own languages. However, many also know and use the word "peyote" as well. Some of the tribes and their common names are:

Comanche—wokowi or wohoki

Cora—huatari

Delaware—biisung

Huichol—hícouri, híkuli, hícori, jícori, and xícori

Kickapoo—pee-yot (a naturalization of the term "peyote" into their language )

Kiowa—seni

Mescalero-Apache—ho

Navajo—azee

Omaha—makan

Opata—pe jori

Otomi—beyo

Taos—walena

Tarahumara—primarily híkuli, but also híkori, híkoli, jíkuri, jícoli, houanamé, híkuli wanamé, híkuli walúla saelíami, and joutouri

Tepehuane—kamba or kamaba

Wichita—nezats

Winnebago—hunka

Numerous other common names have been applied to Lophophora. These include:

Biznaga (= carrot-like or worthless thing)—commonly applied to many globose cacti

Cactus pudding

Challote—used principally in Starr County, Texas, one of the major collecting sites for peyote in the United States

Devil's root

Diabolic root

Dry whiskey

Dumpling cactus

Indian dope

Moon, the "bad seed," "p"—these names have been applied to peyote by drug users in the United States in the late 1970s

Raíz diabólica (= devil's root)

Tuna de tierra (= earth cactus)

Turnip cactus

White mule

Part of the confusion with regard to the numerous common names for Lophophora is because they are frequently applied to and/or taken from cacti of other genera or plants from another family entirely.

PLANTS CONFUSED WITH OR CALLED PEYOTE

Two factors have led to the confusion of various plants and the name peyote: (1) a similarity of appearance because of pubescence, a globose shape, or growth habit, and (2) a similar physiological effect or use for medicinal or religious purposes. In fact, most of the plants that are sometimes called "peyote" possess both of these characters.Many alkaloid-containing cacti are commonly called "peyote" but they are not in the genus Lophophora, and, even though some of the alkaloids are the same, probably they have few or no physiological actions similar to the true peyote. Cacti that have at one time or another been called "peyote" or the Spanish diminutive "peyotillo" are:

Ariocarpus fissuratus—more frequently called "living

rock" or "chautle" but also "peyote cimarr6n."

A. kotschoubeyanus—usually called "Pezuna de venado"

or "pata de venado."

A. retusus—usually called "chautle" or "chaute."

Astrophytum asterias—surprisingly similar in appearance

to Lophophora.

A. capricorne—also called "biznaga de estropajo."

A. myriostigma—called "peyote cimarr6n," "mitra,"

and "birrete de obispo" (bishop's cap or miter).

Aztekium ritterii—another small, globose cactus with

superficial resemblance to Lophophora.

Mammillaria (Dolichothele) longimamma—sometimes called

"peyotillo."

M. (Solisia) pectinifera

Obregonia denegrii

Pelecyphora aselliformis—commonly called "peyotillo"

and sold as such in the native markets. Contains some of the alkaloids

possessed by Lophophora, including small amounts of mescaline.

Strombocactus disciformis—similar in appearance to Lophophora

and occurring in the same general area as L. diffusa.

Turbinicarpus pseudo pectinata

Other plant families, including the Compositae, Crassulaceae,

Leguminosae, and Solanaceae, also have representatives that occasionally

are called "peyote." A member of the Compositae was

first described as a type of peyote by the Spanish physician,

Francisco Hernandez, in his early study of the plants of New Spain.[19]

In his book he described two peyotes: the first, Peyotl Zacatecensi,

clearly was Lophophora, whereas the other, Peyotl Xochimilcensi,

apparently was Cacalia cordifolia, a Compositae which had

"velvety tubers" and was used medicinally. Other sunflowers

of the closely-related genus Senecio have also been called

such things as "peyote del Valle de Mexico" and "peyote

de Tepic."

"Mescal" is the correct name for the alcoholic beverage

obtained from the century plant, Agave americana, but was

also used by missionaries and officials of the Bureau of Indian

Affairs for peyote. Possibly this was an attempt to confuse Congressmen

and the public into thinking that peyote was an "intoxicant"

similar to alcohol, but it just may have been a case of incorrect

information perpetuated unwittingly.

The name "mescal beans" has also been applied incorrectly

to peyote but actually is the common name of Sophora secundiflora

of the Leguminosae. The beans of this plant contain cytisine,

a toxic pyridine that causes nausea, convulsions, hallucinations,

and even death if taken in too large quantities.[20] The colorful

red beans have been used for centuries both in Mexico and the

United States by the Indians for medicinal and ceremonial purposes,

and sometimes the seeds of this desert shrub are worn as necklaces

by the leaders of peyote ceremonies. The stimulatory and hallucinatory

nature of these beans probably led to the confusion with peyote,

especially when the latter occasionally was called "mescal."

The probable relationship of the old mescal bean ceremony and

the modern peyote cult also may have led to confusion by white

men; this relationship is discussed in chapter 2.

Peyote has also been referred to as the "sacred mushroom";

this confusion probably is the result of the similar appearance

of dried peyote tops and dried mushrooms. Also, there are some

mushrooms that can produce color hallucinations similar to those

of peyote. The Spaniards first misidentified peyote as a mushroom

late in the sixteenth century when they stated that the Aztec

substance "teonanacatl" and peyote were the same; this

mistake was perpetuated by the American botanist, William E. Safford.[21]

He and other reputable scientists insisted that there was no such

thing as the sacred mushroom "teonanacatl"; they believed

that it was simply the dried form of peyote. The problem was resolved

when hallucinogenic mushrooms were rediscovered in 1936 and definitely

linked to early Mexican ceremonies. In recent years at least fourteen

species of hallucinogenic mushrooms have been identified in the

genera Psilocybe, Stropharia, Panaeolus, and Conocybe

of the family Agaricaceae. It is evident that they are well known

to Mexican Indians.[22]

Another plant that has occasionally been confused with peyote

is "ololiuhqui," which is now classified as Rivea

corymbosa of the Convolvulaceae. Ololiuhqui has been

widely used by Indians in the Sierra Madre Occidental of Mexico

for many purposes, such as an aphrodisiac, a cure for syphilis,

an analgesic, a cure for colds, a stimulating tonic, a carminative

(to relieve colic), a help for sprains and fractures, and for

relief of pelvic cramps in women.[23] Recent studies have shown

that the plant contains several potent chemicals which are ergot

alkaloids closely related to LSD.[24] Thus, the effects are somewhat

similar to those of peyote: stimulatory at first and later producing

color hallucinations. Indians could easily see many "divine"

actions resulting from ingestion of the seeds of Rivea

and it is not difficult to understand why they and others may

have confused it with peyote, another "divine" plant.

Several Mexican plants and fungi are hallucinogenic like Lophophora.

The following summary gives the ancient Mexican name, the botanical

name or names, the plant or fungus family, and one or more of

the main psychoactive substances: [25]

Picietl = Nicotiana rustica L. (Solanaceae)

A species of tobacco which contains nicotine.

Teonanacatl = Psilocybe spp.

Panaeolus campanulatus L. var. sphinctrinus (Fr.)

Bresad.

Stropharia cubensis Earle

Conocybe spp.

(All of the above are in the family Agaricaceae)

The psychoactive substances are psilocybin and psilocin.

Pipiltzintzinli = Salvia divinorum Epling&Javito (Labiatae)

The psychoactive principle of this plant is as yet undetermined.

Ololiuhqui = Rivea corymbosa (L.) Hall. fil. (Convolvulaceae)

Tlitlitzen = Ipomoea violacea L. (Convolvulaceae)

Both of the above members of the Convolvulaceae contain the ergot

or Iysergic acid alkaloids;

LSD is a synthetic derivative and

is not believed to occur naturally.

Marijuana is one of the best-known and most widely used substances currently classified as a hallucinogen. However, there is serious question whether it actually is a hallucination-producing plant (at least in the way that it is used by most people)—and it is of Old World origin. Marijuana is obtained from the genus Cannabis of the angiosperm family Cannabaceae.[26] It is psychoactive but has quite different effects than does peyote.

MORPHOLOGY

Morphological studies, including microscopic examinations, have provided much information about the evolution and relationships of the cacti. Investigations of both vegetative and reproductive parts support the proposal that Lophophora is a distinct genus consisting of two species.Vegetative parts—The growing point or apical meristem, located in the depressed center of the plant, is relatively large and similar to those found in other small cacti. The young leaf, which arises from the meristem, is difficult to distinguish from the expanding leaf base and subtending axillary bud. The leaf base, usually separated from the actual leaf by a slight constriction, grows rapidly to become the podarium, rib, or tubercle. Thus, the leaf base functions as the photosynthetic or food-producing part of peyote. With sufficient magnification the vestigial leaves of seedlings are often large enough to be identified, but they are never more than a microscopic hump in the vegetative shoot of mature peyote plants.

Spines occur only on young seedlings; adult plants produce spine primordia but they rarely develop into spines.

The caespitose or several-headed condition of the peyote cactus apparently occurs through the activation of adventive buds that appear on the tuberous part of the root-stem axis below the crown. Such growth often is the result of injury and almost always occurs if the top of the plant is cut off. However, some populations of peyote seem to have a greater tendency to develop the caespitose condition than do others.

Epidermal cells, usually five-to six-sided and papillose (nipple-like), have cell walls only slightly thicker than those of the underlying parenchyma cells. Sometimes a hypodermal layer can be recognized early in development, but as the stem matures it does not become specialized and never differentiates from the underlying palisade tissue. Normally the epidermis is covered by both cuticle and wax; the latter substance is primarily responsible for the blue-green or glaucous coloration of L. williamsii. Stomata are abundant, especially on the younger, photosynthetically active parts of the vegetative body. They are paracytic and usually subtended by large intercellular spaces. The subsidiary cells of a stoma usually are about twice the size of neighboring epidermal cells. Trichomes are persistent for many years in the form of tufts of hairs or "wool" arising from each areole. They tend to be uniseriate on the younger areoles but are often multiseriate on older ones.[27]

Ergastic substances are evident in the cortex of peyote. Usually they are druses of calcium oxalate which often exceed 250 microns in diameter, but which rarely are found within one millimeter of the epidermal layer. These anisotropic crystals can be easily seen if fresh or paraffin-embedded sections are examined in polarized light. Mucilage cells do not occur in the vegetative parts of peyote but are found in flowers and young fruits.[28]

The chromosome number of peyote, like most other cacti, is 2n = 22. The root tip chromosomes are quite small, and apparently there is no variation from the basic chromosome number of the Cactaceae which is n= 11.

Reproductive parts—Peyote flowers, in contrast to those of other cactus genera such as Echinocactus and most of the Thelocacti, have naked ovaries or the absence of scales on the ovary wall, a character shared with the flowers of Mammillaria, Ariocarpus, Obregonia, and Pelecyphora. Thus, in Lophophora all floral parts are borne on the perianth tube above the ovule-containing cavity. The flower color of Lophophora varies from deep reddish-pink to nearly pure white; those of L. diffusa rarely exhibit any red pigmentation, making them usually appear white or sometimes a light yellow because of the reflection of yellow pollen from the center of the flower. Development of peyote flowers is much like that of Mammillaria.

Pollen of Lophophora is highly variable. Pollen of the Dicotyledonae tend to have three apertures or pores, while those of the Monocotyledonae usually have only one aperture. Peyote pollen varies greatly in aperture number, the northern population having 0-18 and the southern population 0-6. Though the grains are basically spheroidal and average about 40 microns in diameter, the varying numbers of colpae or apertures produce about twelve different geometric shapes. Such a variety from a single species or even population is rare in flowering plants. The pollen of L. diffusa has less variation than that of L. williamsii; it also has a much higher percentage of grains that are of the basic tricolpate (three-aperturate) type. Thus, the basic dicotyledon pattern is best observed in the southern population, whereas more complex grains occur in the northern localities. Small, tricolpate grains probably are more typical of the ancestors of the cacti and the more elaborate geometric designs of L. williamsii seem to represent greater evolutionary divergence and specialization.[29]

Fruits of peyote are similar to those of Obregonia and Ariocarpus in that they develop for about a year and then elongate rapidly at maturity. The fruits of Lophophora and Obregonia usually have only the upper half containing seeds whereas they are completely filled with seeds in Ariocarpus.

The seeds of Lophophora are black, verrucose (warty), and with a large, flattened, whitish hilum. They are virtually identical to those of Ariocarpus and Obregonia although there are some minor structural differences of the testa.

Lophophora seems to stand by itself in possessing a particular combination of morphological characters unlike any other group of cacti. Its nearest relatives appear to be the genera Echinocactus, Obregonia, Pelecyphora, Ariocarpus, and Thelocactus. The character of seeds, seedlings, areoles, and fruits certainly support the contention that peyote belongs in the subtribe Echinocactanae (sensu Britton and Rose) rather than in the more recently proposed "Strombocactus" line of Buxbaum. Perhaps the poorly understood genus Thelocactus may be the single most closely related group.[30]

BIOGEOGRAPHY

The genus Lophophora is one of the most wide-ranging of all the plants occurring in the Chihuahuan Desert; it has a latitudinal distribution of about 1,300 kilometers (800 miles), from 20 degrees, 54 minutes to 29 degrees, 47 minutes, North Latitude (figure 8.2). Within the United States L. williamsii is found in the Rio Grande region of Texas. There is a small population occurring in western Texas near Shafter; it occurs in the Big Bend region, and then it is found in the Rio Grande valley eastward from Laredo. Peyote extends from the international boundary southward into Mexico in the basin regions between the Sierra Madre Occidental and the Sierra Madre Oriental to Saltillo, Coahuila; this vast expanse of Chihuahuan Desert in northern Mexico covers about 150,000 square kilometers (60,000 square miles). Just south of Saltillo the range of peyote narrows, is interrupted by mountains, and then expands again eastward into the foothills of the Sierra Madre Oriental and westward into the state of Zacatecas. It extends southward nearly to the city of San Luis Potosi where its distribution terminates (figures 8.3 and 8.4). The southern population of peyote, that of L. diffusa, is restricted to a high desert region in the state of Queretaro. This area of about 775 square kilometers (300 square miles) is isolated from the large northern populations by high, rugged mountains (figures 8.5 and 8.6).Three factors apparently are responsible for the discontinuous distribution of Lophophora between the large northern and the smaller southern population: (1) extensive saline flats in the Rio Verde region east of the city of San Luis Potosi, (2) formidable mountains: the Sierra Gorda extension of the Sierra Madre Oriental, and (3) high elevations even in the broad valleys. The relatively high desert area in Queretaro apparently is an isolated pocket of the Chihuahuan Desert.

There are great elevation differences from the north to the south within the total range of peyote; the Rio Grande peyote occurs at an elevation of about 50 meters (150 feet), but in the southern portion of its range in the state of San Luis Potosi it is found at nearly 1,850 meters (6,000 feet) elevation. The elevation of the southern population in Queretaro is about 1,500 meters (5,000 feet).[31]

It is unclear to what extent human beings have affected the distribution of peyote. There are areas where man has collected large quantities of the plant, such as near Laredo, Texas; near Matehuala, San Luis Potosi; and in the dry desert valley area of Queretaro. In 1961 I collected L. diffusa in a region near the road going north from Vizarron, Queretaro; in 1967 I returned to the same area but could find no peyote. Farmers living nearby told us that about a year earlier a man from a nearby village whom they called a "Padre" hired workers to collect all of the peyote that they could find in the region. The farmers didn't know why the man had wanted so many plants or what he planned to do with them, but I doubt that they were used for religious or medicinal purposes. Probably they were sold to cactus collectors—or perhaps even destroyed. Fortunately, peyote is a common and widespread plant and it occurs in many areas that are almost inaccessible. However, we may see considerable disturbance and loss of peyote populations in areas easily reached by man.

ECOLOGY

The Chihuahuan Desert where peyote occurs is a type of warm-temperate desert biome. This region has considerable variation in both topography and vegetation, which has prompted ecologists to describe numerous subdivisions. Unfortunately, these subdivisions are not alike nor have they received the same names. Following the classification of the Mexican botanist, Jerzy Rzedowski, peyote occurs primarily in two subdivisions of the Chihuahuan Desert: ( 1 ) the microphyllous desert scrub, which has shrubs that are leafless or have small leaves and are represented by such plants as Larrea tridentata, Prosopis laevigata, and Flourensia cernua; and (2) the "rosettophyllous" desert scrub, with many plants bearing rosettes of leaves, such as Agave lecheguilla and Yucca spp.[32] Probably neither of these vegetation subdivisions can be considered climax communities, nor even formations, because there is continuous mixing of the two life forms. Since there is such confusion between these two subdivisions, perhaps Cornelius H. Muller's general term "Chihuahuan Desert Shrub" should be used to describe the general area in which peyote occurs.[33]The well-isolated southern population apparently is outside the region normally included within the Chihuahuan Desert. However, the presence of Larrea tridentata and other plants typical of this type of desert is an indication that it should, indeed, be included within the Chihuahuan Desert.

The soils of the Chihuahuan Desert Shrub are limestone in origin and have a basic pH, from 7.9 to 8.3. These soils can also be characterized as having more than 150 ppm (parts per million) calcium, at least 6 ppm magnesium, strong carbonates, and no more than trace amounts of ammonia. The soils test negatively for iron, chlorine, sulfates, manganese, and aluminum. Phosphorus and potassium vary somewhat throughout the range, but in most localities occur in trace amounts or are not present at all. Soils from the southern locality in Queretaro are not different from those to the north.[34]

As stated earlier, peyote occurs in diverse habitats of the Chihuahuan Desert, and no particular plants are associated with it in all localities. Only Larrea tridentata (creosote bush) is found in more than 75 percent of the peyote sites studied; other plants commonly found with peyote and their percentage of occurrence in the sites analyzed are: [35]

Jatropha dioica (leatherplant)—70 percent

Echinocereus spp. (hedgehog cactus)—70 percent

Opuntia leptocaulis (pipestem cactus)—70 percent

Prosopis laevigata (mesquite)—70 percent

Agave lecheguilla (lechuguilla)—50 percent

Echinocactus horizonthalonius (eagle claws cactus)—50

percent

Mammillaria spp. (fishhook or nipple cactus)—50 percent

Flourensia cernua (tarbush)—50 percent

Acacia spp. ( acacia )—40 percent

Condalia spp. (lotebush)—40 percent

Coryphantha spp.—40 percent

Neolloydia spp.—40 percent

Yucca filifera (yucca)—40 percent

Hamatocactus spp.—40 percent

The following plants, supposedly typical of the Chihuahuan Desert, occurred in less than 40 percent of the peyote sites studied:

Coldenia canescens

Euphorbia antisy phylitica ( wax plant )

Koeberlinia spinosa (crucifixion thorn)

Of course not all perennial plants growing with peyote have been

cited, but this information indicates that peyote occurs over

a broad range of vegetation types within the Chihuahuan Desert.

The climatic data from the regions in which peyote grows have

been analyzed to obtain an "index of aridity." Using

the index of aridity devised by Consuelo Sota Mora and Ernesto

Jauregui O. of the University of Mexico, [36] peyote is found

to tolerate a very wide range of climatic conditions: precipitation

ranges from 175.5 mm up to 556.9 mm per year, maximum temperatures

vary from 29.1 degrees centigrade to 40.2 degrees, and minimum

temperatures range from 1.9 to 10.2 degrees centigrade. There

is also a variation in the time of year that precipitation occurs.

Rains typically fall in the late spring and summer in the Chihuahuan

Desert, but in certain areas some winter rains do fall. There

are peyote populations in both types of areas, so probably they

should be classified as being in intermediate rather than strictly

summer rainfall regions. The modified index of aridity, which

is based on the relationship of temperatures and precipitation,

shows that Lophophora exhibits a wide range of aridity,

between 64.0 and 394.0. It also appears that the index of aridity

is related to elevation, although there are some definite exceptions,

such as in Queretaro, where there is a relatively high elevation

(about 1,500 meters or 5,000 feet) but an index of aridity that

is over 115. This southern habitat, though of high elevation,

may be especially arid because of the proximity of surrounding

high mountains which cause a more intensified rain shadow.

CHARACTERISTICS OF PEYOTE POPULATIONS

Peyote consists of populations that are not only wide-ranging geographically, but which are also variable in topographical locations, appearance, and methods of reproduction. Commonly peyote is found growing under shrubs such as Prosopis laevigata (mesquite), Larrea tridentata (creosote bush), and the rosette-leafed plants such as Agave lecheguilla; at other times, however, it grows in the open with no protection or shade of any kind. In some areas, such as in the state of San Luis Potosi, peyote sometimes grows in silty mud flats that become temporary shallow fresh-water lakes during the rainy season. In west Texas peyote has even been found growing in crevices on steep limestone cliffs.The appearance of peyote also varies widely, especially in the species L. williamsii. In some cases the plants occur as single-headed individuals and in others they become caespitose, forming dense clumps up to two meters across with scores of heads. Plants in Texas do not seem to form clumps as often as those in the state of San Luis Potosi, but plants with several tops can arise as the result of injury by grazing animals or other factors. Many-headed individuals are also produced by harvesting the tops. In Texas, for example, collectors normally cut off the top of the plant, leaving the long, carrot-shaped root in the ground; the subterranean portion soon calluses and in a few months produces several new tops rather than just a single one like that which was cut off.

The number of ribs present in a single head varies widely, rib number and arrangement apparently being in part a factor of age, as well as a response to the environment. Rib number within a single, genetically identical clone may vary from four or five in very young tops up to fourteen in large, mature heads (figure 8.4). At other times there are bulging podaria instead of distinct ribs. Field studies have shown that rib number and variation apparently are due to localized interactions between genotype and environment. Because of the high degree of variation occurring in a single population, rib characteristics alone are of little value in the delimitation of formal botanical taxa.

Reproduction occurs mainly by sexual means. The plants flower in the early summer, and the ovules, which are fertilized during that season, mature into seeds a year later. The fruit which arises from the center of the plant late in the spring or early in the summer rapidly elongates into a pink or reddish cylindrical structure up to about one-half inch in length. Within a few weeks these fruits mature; their walls dry, become paper thin, and turn brownish. Later in the summer, usually as a result of wind, rain, or some other climatic factor, the fruit wall ruptures and the many small black seeds are released. The heavy summer rains then wash the seeds out of the sunken center of the plant and disperse them.

Another method of reproduction in peyote is by vegetative or asexual means. Many plants produce "pups" or lateral shoots which arise from lateral areoles. After these new shoots have attained sufficient size they can often root and survive if broken off. If these new portions successfully grow into new plants, they are genetically identical to their parents. Surprisingly, peyote plants rarely rot if injured or cut, so excised pieces will readily form adventitious roots and can become independent plants.

EVOLUTION OF PEYOTE

The evolutionary history of the cacti is not documented by fossils because their succulent vegetative parts did not lead to preservation as fossils in the dry climate. The highly specialized cactus has few distinctive characteristics that probably were present in distant ancestors, but it does appear that the tropical leafy cactus, Pereskia, may represent a form that has changed little from the non-cactus ancestral types. It and many of the more specialized cacti have many characteristics similar to the other ten families of the order Caryophyllales (Chenopodiales) in which the cacti are often placed. Most of these families, for example, have a curved embryo, the presence of perisperm rather than endosperm, either basal or free-central placentation, betalain pigments rather than the usual anthocyanins, anomalous secondary thickening of the xylem walls, and succulence.[37]The evolutionary picture from Pereskia is only hazy at best, although Pereskiopsis seems to represent an intermediate form in the Opuntia line. The "barrel" or "columnar" cacti, on the other hand, show virtually no links to one another or to any of the more "primitive" cacti such as Pereskia or Pereskiopsis. Apparently the living representatives of the cacti are terminal points of a highly branched evolutionary history, and ancestors no longer exist. Therefore, we must work with characters of living representatives to draw any conclusions regarding the past evolutionary history of the cacti, a procedure of speculation at best.

Certain evolutionary trends appear evident in the two species of peyote. Pollen of L. diffusa, because of its higher percentage of the basic tricolpate type of grain, could be considered more primitive than that of L. williamsii. Likewise, James S. Todd and other chemists have shown that certain of the more elaborate alkaloids are either absent or in lesser amounts in L. diausa.38 This, they feel, indicates that L. diffusa may not have evolved and diversified to as great an extent chemically as has L. williamsii. Also, the greater variation of the vegetative body of L. williamsii, in addition to more varied habitats and a wider distribution, perhaps show a more diverse and highly evolved gene pool.

Lophophora probably arose from a now-extinct ancestor that occurred in semi-desert conditions in central or southern Mexico. Morphological and chemical diversity may have then appeared in various populations as they slowly migrated northward into drier regions which were being created by the slow uplift of mountains. Perhaps L. diffusa represents one of the earlier forms that became isolated in Queretaro, whereas L. williamsii spread more extensively to the northward, producing new combinations of genes that eventually led to a distinct but highly variable species having somewhat different pollen, vegetative characters, and alkaloids from the peyote populations to the south.

CULTIVATION

Peyote is easily cultivated and is free-flowering. On the other hand, one must be very patient if he wishes to grow peyote from seed, as it may take up to five years to obtain a plant that is 15 millimeters in diameter. At any stage, however, peyote can be readily grafted onto faster-growing rootstocks, and this usually triples or quadruples the plant's rate of growth. Japanese nurserymen, for example, have obtained peyote plants large enough to flower within a period of 12-18 months by grafting the young seedlings onto more robust root stocks.To insure the obtaining of fertile seed, it is advisable to out-cross peyote plants by transferring with forceps some stamens containing pollen from the flower of one plant to the stigma of the flower of another.

Propagation can also be accomplished by removing small lateral tops from caespitose individuals. The cut button or top should be allowed to callus for a week or two and then planted in moist sand or a mixture of sand and vermiculite. It is wise to dip the freshly cut portion in sulfur to facilitate healing. Rooting is best done in late spring or early summer. Eventually a new root system will develop from the top; the old root will produce several new heads to make a caespitose individual.

Soil conditions for the cultivation of peyote are not too critical. As the natural soil for peyote is of limestone having a basic pH, one should provide adequate calcium, insure that the soil is slightly basic, and provide good drainage. Peyote should be watered frequently (every four to seven days) in the summer but very little or none at all in the winter. Fertilizer should be applied while the plants are being watered during the growing season, especially May through July.

Peyote hosts few insect pests and does not need to be treated differently from other cultivated cacti and succulents with regard to pesticides.

Greenhouse-grown peyote plants sometimes develop a corky condition; this brownish layer often covers most of the plant and is not natural. Its cause is not known.

The propagation of seeds is a rewarding experience but requires great patience. Seeds should be sowed on fine washed sand and then covered with one to two millimeters (about one-eighth inch) of very fine sand. Cover the flat or pot with a plastic bag or plate of glass and place an incandescent light (60 watt) or Grolux lamp about twelve inches above the sand. These provide both heat and light. The sand should be kept moist to insure that the humidity is high and that the young plants will not dry out as they first sprout. Germination usually occurs within two or three weeks but growth of the seedlings is exceedingly slow. The plants should be transplanted and thinned after they are about one centimeter (one-fourth of an inch) in diameter.

Most states, as well as the federal government, now prohibit the possession of peyote (see chapter 9), and apparently one is in violation of the law even if peyote is grown as part of a horticultural collection.

NOTES TO CHAPTER 8

1. Jan G. Bruhn and Bo Holmstedt, "Early Peyote Research: An Interdisciplinary Study," pp.384-85.2. William Jackson Hooker, "Tab. 4296. Echinocactus Williamsii."

3. Theodor Rumpler, Carl Friedrich Forster's Handbuch der Cacteen kunde, p. 233.

4. Charles Lemaire, Cactearum Genera Nova et Species Nova en Horto Monville, pp. 1-3.

5. J. Lanjouw and others (eds.), International Code of Botanical Nomenclature, p. 50.

6. Bruhn and Holmstedt, "Early Peyote Research," pp. 358-60.

7. Paul Hennings, "Eine giftige Kaktee, Anhalonium lewinii n. sp.," p.411.

8. Edward F. Anderson, "The Biogeography, Ecology, and Taxonomy of Lophophora (Cactaceae)," pp. 305-06.

9. Bruhn and Holmstedt, "Early Peyote Research," pp. 384-85.

10. John M. Coulter, "Manual of the Phanerogams and Pteridophytes of Western Texas," p. 129.

11. A. Voss, "Genus 427. Ariocarpus Scheidw. Aloecactus," p. 368.

12. John M. Coulter, "Preliminary Revision of the North American Species of Cactus, Anhalonium, and Lophophora," pp. 131-32.

13. Anderson, "Biogeography, Ecology, and Taxonomy," pp. 299-303.

14. Fr. Bernardino de Sahagun, Historia General de las Cosas de Nueva Espana, X, p. 118.

15. Richard Evans Schultes, "Peyote (Lophophora williamsii) and Plants Confused with It," pp.61-88.

16. Ibid.

17. A. de Molina, Vocabulario de la Lengua Mexicana, p. 80.

18. R. Gordon Wasson, "Notes on the Present Status of Ololiuhqui and the Other Hallucinogens of Mexico," pp. 166-67.

19. Francisco Hernandez, De Historia Plantarum Novae Hispaniae, pp. 70-71.

20. Richard Evans Schultes and Albert Hofmann, The Botany and Chemistry of Hallucinogens, p. 99.

21. William E. Safford, "An Aztec Narcotic," p. 311.

22. Schultes and Hofmann, Botany and Chemistry of Hallucinogens, pp. 36-39.

23. Hernandez as reported in Schultes, "Peyote and Plants Confused with It," p.74.

24. Schultes and Hofmann, Botany and Chemistry of Hallucinogens, pp. 144-51.

25. Wasson, "Notes on Ololiuhqui," pp. 164-75.

26. Richard Evans Schultes, William M. Klein, Timothy Plowman, and Tom E. Lockwood, "Cannabis: An Example of Taxonomic Neglect," pp.360-62.

27. Norman H. Boke and Edward F. Anderson, "Structure, Development, and Taxonomy in the Genus Lophophora," p. 573.

28. Ibid., pp.573-74.

29. Edward F. Anderson and Margaret S. Stone, "A Pollen Analysis of Lophophora (Cactaceae)," pp. 77-82.

30. Boke and Anderson, "Structure, Development, and Taxonomy," p. 577.

31.Anderson, "Biogeography, Ecology, and Taxonomy," pp. 301-02.

32. Jerzy Rzedowski, "Vegetacion del Estado de San Luis Potosi," pp. 219-20.

33. Cornelius H. Muller, "Vegetation and Climate of Coahuila Mexico," p. 38.

34. Anderson, "Biogeography, Ecology, and Taxonomy," p. 302.

35. Ibid., pp. 302-03.

36. Consuelo Soto Mora and Ernesto Jaurequi O., Isotermas Extremas e Indice de Aridez en la Republica Mexicana, pp. 26-28.

37. Arthur Cronquist, The Evolution and Classification of Flowering Plants, pp. 177—80.

38. James S. Todd, "Thin-layer Chromatography Analysis of Mexican Populations of Lophophora (Cactaceae)," pp. 395-98.

Figure 8.2

Natural distribution of the two species

of peyote, Lophophora williamsii and Lophophora diffusa.