|

|

|

|

77

Confusion over Cannabis in Yunnan

Introduction

Yunnan Province, in the southwest of the People's Republic of China, bordering Myanmar (Burma), Laos and Vietnam, is home to many of China's minority nationalities. Although the Han majority have largely given up hemp usage in daily life, several of Yunnan's minority ethnic groups continue to use hemp for both fiber and food. However, there is very little consumption of Cannabis products for recreational purposes by either resident Chinese or visitors. Despite these facts, the Yunnan provincial government has instigated policies that confuse drug Cannabis ("marijuana") with industrial hemp. Since the spring of 1998, the growing of Cannabis for any reason has been prohibited, although Cannabis still flourishes in most parts of Yunnan. Confusion continues.

In July through August of 1999, and again in February through April of 2000, I traveled to several regions of Yunnan Province to survey the occurrence of wild, agricultural and feral Cannabis populations and speak to minority groups about their traditional usage of hemp. During this time, rural peasants frequently commented on the new hemp prohibition policy. This paper reports the occurrence and use of hemp in Yunnan and will investigate the impact of hemp prohibition on its minority nationalities.

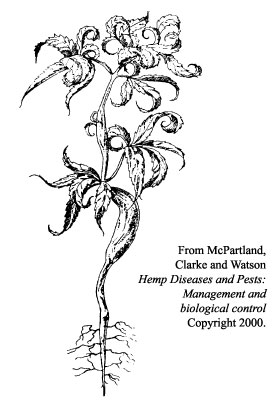

Figure 1. Ornamental Cannabis growing prominently along

a busy Kunming street.

Occurrence of hemp in Yunnan

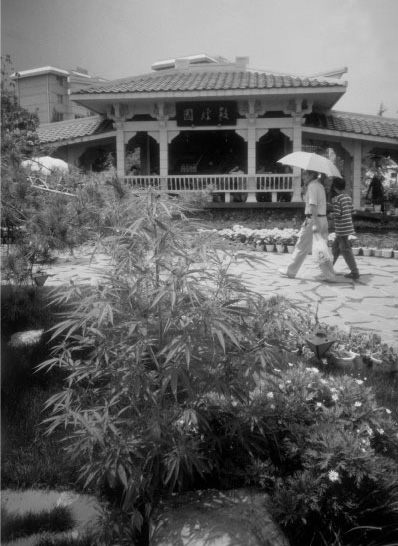

Populations of a few to several hundred Cannabis plants can be seen throughout much of urban and rural Yunnan along roadsides, railroad tracks and trails, in vacant lots, construction sites and dumps, and near habitations and watercourses which provide adequate sunlight, disturbed soil and increased soil nutrients. Most plants are apparently feral, but some are carefully tended, especially those residing in obvious splendor in front of shops and restaurants (Fig. 1). These most often grow as large solitary specimens, trimmed of lower branches and supported by canes and ties. Some plants, such as large solitary males, are grown simply for their ornamental value and are often accompanied by large showy flowers such as amaranth, dahlia or sunflower. Large hemp plants are seen along busy thoroughfares and other prominent locations in Yunnan's capital city Kunming. For example, at the China International Horticultural Expo held in Kunming beginning in May of 1999, several Cannabis plants were evident throughout the summer. Two robust male plants over 3 meters tall were sprawled across the end wall and ceiling just inside the entrance of the impressive "Butterfly House". Beautiful butterflies flocked to the hemp plants and many of the leaves had served as food for their hungry larvae. These large specimens must have been planted before the Expo opened. Another was a male plant over one meter tall growing outdoors in the central landscape of the Gansu Province pavilion, thoughtfully placed next to a comfortable polished boulder where Chinese visitors regularly sat for the ever-popular portrait opportunity (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Cannabis growing at the China International

Horticultural Expo in Kunming, July 1999.

Hemp industry in Yunnan

Most of the hemp crops grown in Yunnan (approximately 75%) are destined for seed production. Seed plants are most often dispersed within, or grown along the borders between, other crops such as maize or beans. Provided with sufficient space to grow, they branch profusely and the females produce large amounts of flowers and seed. Densely sown fiber crops of tall thin plants with no branches are much less common.

Hemp products of many sorts are available in the markets of Yunnan Province, as they are in many regions of China. The most commonly seen items are raw or toasted hemp seeds offered along with other snack seeds. Hemp seed is also a valuable animal feed, especially for poultry. Raw hemp bark is sold for caulking and binding material. Processed bark is twisted or plaited into many sizes of twine and rope. Hemp textiles are still produced both by village weavers and textile factories and are available in the local markets. Traditional hand woven cloth is frequently an item of trade between active hemp weaving minorities such as the Miao and others who have almost entirely given up hemp weaving, such as the Han.

It is difficult to estimate the size of Yunnan's hemp industry, but there are several indications that it is of some economic significance. In the Wenshan and Gejiu areas of southern Yunnan, hemp is grown both for fiber and seed. The textile mill in the town of Gejiu continues to spin and weave hemp for the domestic and export trades, but hemp is a small portion of their total production. In 1997-99 the Yunnan government sponsored a poverty alleviation program to provide assistance to rural peasants by buying selected agricultural products. Between 800 and 2000 tons of hemp seed were purchased each year and stockpiled in an agricultural products warehouse for later sale, largely for export to animal feed companies in China and abroad. The seeds are purchased for about ¥2 (US$0.25) per kg and sell for about ¥4 (US$0.50) per kg. This program has continued through the first three years of hemp prohibition. Rural minority groups in this region would likely suffer from enforced hemp prohibition.

Hemp is not seen by all to be a useful and economically significant crop. Although almost all of the minority nationalities and the majority of rural Han peasants traditionally grew hemp, the majority of them have steadily given up hemp growing during the past 30 years. "We have not grown hemp since 'Modern China' began." (1949), is a frequently heard comment. In a modern market society, hemp cultivation and processing are simply too much work compared to purchasing cloth and cordage. Those who continue to grow hemp, do so either for cultural reasons or because they are too poor to purchase market goods. Officials generally register a disinterested reaction to any questioning of hemp prohibition. As far as most are concerned, the hemp mills can change over to spinning and weaving ramie (Boehmeria sp.) which grows well in many parts of Yunnan. Few Chinese wear hemp any longer and people can eat sunflower seeds, pumpkin seeds, soybeans, pine nuts and peanuts for snacks. Most are convinced that hemp really will not be missed.

History of hemp prohibition

The hemp prohibition policy has not been implemented evenly. The first "red head letter", or official government notice, of hemp prohibition came to many areas of Yunnan in the spring of 1998, but most areas did not hear about it until spring, 1999. A few areas actually learned of the prohibition for the first time from this investigator in the summer of 1999, but these were not Miao (who had heard about it the previous year). Prohibition continued in the spring of 2000.

The government in Malipo County, along the Vietnam border, still allows hemp growing in this economically poor area. However, most of the Miao men support hemp prohibition because they feel hemp processing and weaving takes too much of the women's time and the village land that could better be better used for food production. The Miao women, however, do not want to give up weaving hemp cloth, as their clothes are made from it, their ritual traditions depend on it, and it provides them with extra income. Since agricultural land is scarce, the Malipo Miao can grow less hemp themselves, but continue to weave cloth and sell it by importing yarn from the Vietnamese Hmong (Miao) who grow hemp and spin it.

The Miao, and other ethnicities, have traditionally employed hemp for a wide variety of common daily uses as well as special rituals. Hemp fiber is presently used for cordage, sacking and clothing, hemp seed is used for its nutritious oil, "bean" curd, porridge and snacks, and the leaves, seeds and roots are used to prepare medicines. Hemp fiber and seed are also included in life-cycle rituals surrounding birth, marriage and death (Clarke and Gu 1998).

Hemp prohibition has indeed been felt by some Miao who were fined and whose crops were destroyed. Earlier in the spring each of the past three years, the village leaders had sent representatives to inform the Miao that hemp growing was now illegal. Most of the village residents who removed their crops when first warned by the authorities were not fined. Families who continued to grow hemp after being warned had their crops destroyed and were fined as much as ¥200 (US$25).

These villages used to weave hemp cloth and sell it to other Miao who had given up weaving. They have now lost valuable income. They are angry about both the interruption of their long-standing traditions and the loss of trade income. There is no tobacco grown in many Miao regions and tea is only for local consumption, so there are very few possibilities to earn a cash income.

It is difficult to determine if hemp prohibition targets the Miao more than other minority nationalities, as they are the only minority to be so actively and openly continuing to practice their hempen traditions. However, there are still many other minority nationality and Han farmers scattered around Yunnan who grow hemp for subsistence and commerce, and they add up to a much larger total population than the Miao alone.

Some respondents predict that the Miao may be allowed to grow hemp and process it for fiber or seed, for home use only, but they will not be allowed to trade in hemp cloth or clothing. In this way, the Miao may be persuaded to gradually give up their hemp traditions. Others argue that if the Miao continue to grow hemp they will start to use it for drugs. However, this seems a rather unlikely scenario for a minority ethnicity with a strong hemp tradition, no tradition of Cannabis drug use and no drug Cannabis varieties. Drug Cannabis (marijuana and hashish) cannot be produced from hemp seeds.

Miao farmers are being told to destroy their hemp fiber crops, as are some rural Han and other ethnic groups, yet "pet" ornamental plants growing in isolation or in small groups, as well crops for seed production, can be seen along major roads throughout Yunnan. These female plants could be grown without seed by simply removing the male plants, and could be sold as low quality seedless marijuana. However, no publication or law enforcement agency has reported any seedless Cannabis coming from Yunnan, and it is impossible to grow potent marijuana from local hemp varieties even if they are grown seedless.

Authorities have claimed some success in eradicating Cannabis from certain locations (Shen Xing Huo Bao, 2000). However, the government may find hemp more difficult to control in some areas than they anticipate.

"Marijuana" in Yunnan

There is only one location in Yunnan where Cannabis is used in a drug-related context. Feral Cannabis grows abundantly throughout the hills above Dali town, a popular tourist destination in western Yunnan. During the early 1990s, when the first backpacker tourists on the Dali-Lijiang-Tiger Leaping Gorge route saw feral hemp growing, they harvested small amounts, which they dried and smoked. The local Bai minority market women soon realized that they could harvest as much as they wanted of the naturally growing "marijuana" in the autumn and sell it to tourists all year long. The Dali Bai have no tradition of recreational Cannabis consumption and they do not have a recent history of hemp cultivation, although they were active opium producers before the founding of Modern China. The Bai market women also sell "hemp" clothing to tourists which is made from cloth imported from the commercial hemp producing areas of Yunnan and other provinces. Although hemp is not a traditional part of their culture, they realize that hemp sales are good business, as is selling "marijuana" to tourists. Small amounts of dried Dali Cannabis leaf and flowers are occasionally taken to Kunming and other areas of Yunnan by tourists, where they smoke it.

Eventually, Dali gained an obscure international reputation as a source of marijuana. Both High Times (1994) and Cannabis Culture (1999), recreational Cannabis magazines, spread the image of Dali as an attractive tourist destination for Cannabis smokers. In actuality, Dali and other feral Yunnan Cannabis contains very little psychoactive THC (less than 2% dry weight) and so is of very low potency compared to Western drug (2-25% THC) Cannabis (Clarke 1998). The perceived "high" of feral Yunnan hemp is induced more by wishful anticipation, combined with an exotic Chinese set and setting, than by its actual potency. It is truly a pity that misled Western travelers couldn't have enjoyed writing about one of their more characteristically Chinese experiences, rather than misinterpreting both Cannabis botany and Chinese culture.

Tourism is among Yunnan's most important and fastest growing industries, and Dali is one of Yunnan's most popular tourist destinations. Arresting tourists for marijuana possession would not assist Yunnan Province to bolster tourism. It will be interesting to see how the Dali situation is handled.

Cannabis "drug problem" in Yunnan

Is Cannabis causing a drug problem in Yunnan? In March 1998, I attended a large public exhibit held in Kunming to highlight the successes of the Yunnan drug eradication program. The focus was almost entirely on opiates such as heroin, Yunnan's major, and well known, "hard drug" problem. There was minor coverage of "pills" and other drugs, but absolutely no mention of Cannabis.

A very few Chinese might occasionally be exposed to Cannabis smoking at the cafes and discos frequented by expatriates and tourists. Government officials and police visit night spots just like Chinese residents from other walks of life, and it is apparent that Kunming and Dali police are aware of even a minimal amount marijuana smoking. The Chinese express no tolerance of drug use and the Kunming police have recently issued strong warnings to the owners of the few cafes and clubs where Cannabis might be smoked. Foreigners smoking Cannabis in public are setting a bad example and compromising their personal safety through their indiscriminate actions. Only a very few urban Chinese have begun to smoke, because it is not culturally accepted and therefore of little attraction. In addition there is no local supply of drug Cannabis.

Conclusions

The origin of Yunnan's Cannabis "problem" is rooted in the dichotomy of the West's shallow understanding of Cannabis as an industrial crop. The Yunnan government's new prohibition policy may well be an over-reaction to United Nations and World Trade Organization pressure on China to control its escalating drug problems, stemming almost entirely from hard drug use. However, the UN Single Convention Treaty (1961) specifically exempts Cannabis used for non-drug purposes from its drug statutes. In addition, the UN strives to guarantee the cultural rights of all ethnic groups, including their traditional choice of crop plants. It is difficult to imagine that either the education of Yunnan's school children, or the efficiency of their work force, is effected in the slightest by marijuana use.

It is also possible that the current prohibition of all Cannabis growing in Yunnan, including industrial hemp, results in part from the government's reaction to the Dali backpacker marijuana situation and the occasional smoking of Cannabis in other tourist areas. The Yunnan government has taken a typically Western approach to the situation by instigating a blanket prohibition of Cannabis for all uses. This may be more understandable when seen as a response to a Western-created situation.

Those who suffer the most from prohibition are the rural peasant Han and minority nationalities (e.g. Miao and Yi) who have used hemp's strong fibers and nutritious seeds for generations and have absolutely no cultural tradition of Cannabis use for recreational drugs. Now Cannabis cultivation, even for well-established traditional uses, has been prohibited. This strips the Yunnan Miao and others of both their cultural identity and a supplementary income derived from hemp growing, while doing nothing to stop tourists from buying dried "marijuana" flowers on Dali streets.

References

Anonymous 2000. in Shen Xing Huo Bao (New Life Newspaper) Kunming: July 26.

Allen, Greg 1999. China High. Cannabis Culture No. 18: 56-59

Clarke, Robert C. and Wenfeng Gu 1998 Survey of hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) use by the Hmong (Miao) of the China/Vietnam border region. Journal of the International Hemp Assoc. 5(1): 1, 4-9.

Clarke, Robert C. 1998. HASHISH! Red Eye Press, Los Angeles: 372 pp.

Gorman, Peter 1994. Dali: An oasis in China. High Times (September): 52.

United Nations 1961 Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs. UN Doc. No. E.77.XI.3: 33.