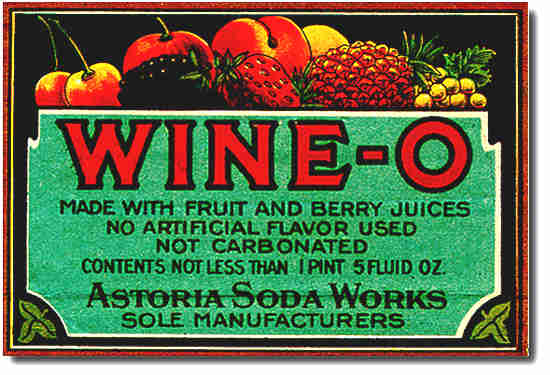

The prohibition years created new possibilities for those with good imaginations. For the enterprising who were determined to stay within the bounds of the law there were commercial opportunities. Many attempted to evoke fond memories of the period before prohibition. They formulated a variety of non-alcoholic drinks that prominently included words clearly associated with liquor, such as those seen here. Some businesses that had been active in the liquor industry scrambled to find new ways to stay afloat. Henry Weinhard's, a large Portland brewery, bought out Puritan Manufacturing Company and thereby gained the rights to manufacture such non-alcoholic beverages as Ras-Porter, Graport, Loganport, and Cherriport. Others simply let their frustration show in the period just after prohibition took effect. Jesse Day of Prineville was apparently so disgusted that he registered a trademark with the title "Nothing." In what must have been a biting commentary on the times, the trademark was to apply to a "temperance beverage."

Opportunities also existed for those who were willing to stretch or break the law. And, at least some of the time, law enforcement officials caught them. The effects of the ban can be seen by examining records such as still registrations. While not able to locate every illegal still, officials carefully tracked those used for legal purposes. Police reports also documented extensive surveillance by state prohibition officers, sheriff's deputies, and others. These often led to arrests and fines as was the case for Arthur Pederson who, unlike his drinking friends, was unable to evade capture. Officials were assisted in their efforts to "stamp out bootlegging" by informants who provided details about illegal organizations operating in Oregon. It was an informant's tip that landed Richard Sargent in the county jail, five hundred dollars poorer. His partner, who later escaped, told deputies that they couldn't go upstairs because there was a sick person there. Instead, they found Sargent with an elaborate still. However, his partner may not have been lying - Sargent was released early from the county jail because he was suffering from tuberculosis. |