|

|

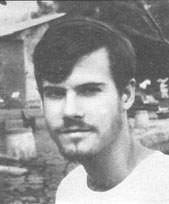

FRANK PROVOST LaVARRE

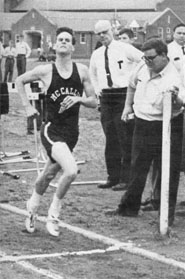

3909 Whitland Ave., Nashville, Tenn. Enrolled September 1963 Captain, A Company; Best Drilled Company, 2; Dunlap Rifles, 3; prefect, YMCA, 2, 3, 4; TEPS, 2; Keo-Kio, 4; Monogram Club, 1, 2, 3, 4; Spanish Club, 2, 3; Tornado, 3, 4; Pennant, 2, 3; Photography Editor, 4; Photography Club, 2, 3, President, 4; Fellowship of Christian Athletes, 3, 4; Dramatics, 2, 3, 4, Scuba Club, 2, 3, 4; Walker Casey Award; Varsity Cross Country, 1, 2, 3, 4; Captain, 4; All Mid-South, 1, 2, 3, 4; Most Improved, 1; Most Valuable Runner, 2, 3, 4; Varsity Track, 2, 3, 4; All Mid-South, 3, 4; Monogram Club Award; Clifford Barker Grayson Memorial Medal; will attend the University of Virginia. | For the long-distance runner

who got caught—a 20-year sentence

AT PREP SCHOOL IN COLLEGE |

by JANE HOWARD

Long-distance running is what Frank LaVarre misses as much as anything, now that he sits in the Danville, Va. city jail serving a 20-year sentence for possessing marijuana.

At his Tennessee preparatory school, Frank broke several track and cross-country records. When he entered the University of Virginia on a full scholarship in 1967, the track coach was glad to see a boy whose idea of a vacation was to ride a bicycle all the way to North Carolina. Often, for the joy of it, Frank ran alone through the Virginia woods—as many as 15 miles a day. Last year, the Rapier, an off-campus literary magazine, pretended to have stolen the flame from the Olympic Games in Mexico, and sought relay runners to take a torch supposedly fit from that flame from the Charlottesville campus to the Mexican embassy in Washington, D.C. Most volunteers did one-mile stints; Frank ran eight, nonstop.

But his next long-distance run was not on his own legs but in a Trailways bus, and his cargo was not a torch but three pounds of what court records were to call "a brown-green grasslike substance"—marijuana. In the Commonwealth of Virginia the minimum penalty for possessing more than 25 grains (about half a teaspoonful) of marijuana is 20 years, the same as the minimum penalty for first-degree murder.

Frank LaVarre was arrested in the Danville bus station Feb. 24, 1969. His bus was bound for Atlanta, where friends awaited the marijuana they had wired him $700 to buy. Acting on a tip from the police chief in Charlottesville, 110 miles north, where Frank had boarded the bus, Danville detectives took him into custody. In jail, he was invited to "cooperate" by divulging names of all university students he knew of who used drugs. As Frank declined to do this, his bond was raised from $5,000 to $8,000 to $50,000.

In court, he pleaded guilty. On July 30, after several hearings, Judge Archibald Aiken sentenced him to 25 years in the penitentiary, with five years suspended for good behavior. "Now, I want to say to you, young man," the octogenarian judge proclaimed, "that you still have time to mend your ways and make a useful citizen out of yourself." By this the jurist presumably meant that with luck Frank LaVarre might be eligible for parole after only five years, a quarter of his unsuspended sentence. That thought did not console Frank's mother and other kin in Nashville, Tenn. They feared the exposure to veteran criminals and homosexuals that the 20-year-old boy, who had never so much as stolen a hubcap, could expect in the penitentiary.

Until three weeks before his arrest Frank LaVarre had never tried marijuana. "I used to think grass was oh-oh, horrible, dangerous stuff," he says. But he kept hearing a lot of talk to the contrary—in Europe, where he spent a summer, and on campus. He heard it was "a nice way of relaxing and opening your senses, of getting into a real nice thing very quickly, with no hangover." He heard it would deepen his already keen sensitivity to music and arts. Still skeptical, he made many trips to the medical school library to, read all he could find on the subject. (He forgot, however, to read about drug laws.) "He prepared for getting stoned," one of his friends says, "the way you'd prepare for a trip to the moon."

Finally convinced it wouldn't harm his body or his head, Frank tried marijuana and liked it. "When Frank liked something," that friend continues, "he liked it super." So it was with photography ("He'd stay all night working in the darkroom, and hang around all day at train stations taking pictures of old colored guys"), and music (Frank's taste had switched from Mahler to Bob Dylan) and food (he liked to astound his friends by cooking escargots and beef Stroganoff) So it was with his own dark brown hair, which to the woe of his elders grew down to his shoulders.

"I'd have grown it long sooner," says Frank, who has since had a prison crew cut, "but, see, McCallie is a semimilitary school." At McCallie, his preparatory school in Chattanooga, Frank was short-haired and exemplary. "He is very personable," his headmaster wrote to whatever college admissions officers it might concern, "a boy of high ideals and character, cooperative, loyal, interested in good literature and artistic things—a well-rounded, fine young man."

Two years later the fine young man was in police custody, being asked to name names. "I guess they figured Frank for a big-time head, the brains behind a ring of dope pushers, who was planning to make a big profit," a friend speculates. "But he wasn't even going to earn his bus fare. He was incredibly naive. In a way I envied his innocence. Friends asked him to carry them some pot, and he didn't want to be the low man on the T.P.—totem pole—so he was going to do it."

"He may not have been pushing," says one Danville official, "but he was doing right much transporting." Right much indeed-enough so that the court was little swayed by the 50 or so letters that poured in commenting on the boy's dazzling potential, lamenting his unlawful act, and respectfully requesting leniency. One letter offered to arrange group therapy sessions if the boy could be paroled to Nashville. Another, from a corporation president, offered him a job. "We need young men like him," the letter said.

Though some of Frank's friends regard him now as a romantic martyr-hero, others make it clear that he is, as one says, "no rose." Frank "didn't always make his bed or balance his checkbook," his roommate says. "Sometimes he'd do things, like letting his hair grow, just to rile people." He also was suffering an extreme case of a syndrome known to his mother as a Sophomore Slump, and to his contemporaries as a Freakout, or Zapout. His grades had slipped so badly that the university had suspended him for a semester.

Frank hoped to work that semester as a photographer in Atlanta. His arrest en route there was instigated by a tip to the Charlottesville police chief. The tipster, suggests a classmate, "had to be a close friend of Frank's, who was worried about him and thought it would be doing him a favor to get him busted. Some favor."

"I think it was a nark [undercover narcotics agent]," another classmate speculates. "Remember, Frank was a loudmouth. All his broadcasting around town about how great grass was could have got to the wrong ears. With pot, he was like a kid with a new go-cart: cautious at first, but then reckless. He wouldn't listen when I told him it was conceivable to be busted. The funny thing is, he didn't need grass to turn on with. Before he ever tried it he'd just sit sometimes and stare at a candle."

"I've always been," as Frank says, "a staunch individualist," And so the individualist was into pot, with as much abandon as he had got into photography and Buddhism.

Now he has plenty of time to read of Zen and Gandhi and Asian wisdom, jailed in a city where the phone book lists 208 clergymen and 124 churches to serve 49,900 souls, where a boy recently died from inhaling Bactine sprayed into a paper bag.

Danville people fear, as a prominent citizen puts it, "that the marijuana seed might get loose and grow wild in this part of the country.

"It worries the goose eggs out of me," the man says. "But we're not going to put up with any foolishness, and everybody knows it."

An honor student at the university disagrees. "The older generation had better get used to pot," he says, "because it's here, and I don't think it's going anywhere. If they're going to lock up people like Frank LaVarre, they're going to have a violent revolution on their hands."

"We went to college in the Depression," says Frank's mother, "but these kids had so much handed to them on a silver platter." She and her husband, who died six years ago of cancer, gave their three children an exceptional childhood. Mr. LaVarre represented the Singer Company in South America, and raised his family there in what apparently was a cheerfully bilingual atmosphere, with servants, and, as Frank puts it, "a lot of cultural enrichment."

It puzzles many people that so promising a scion of so enriched a background should now face two decades—or at the very least five years—behind bars. Among the puzzled is a minister in Danville, who comments that "the law Frank was tried under was meant to catch very heinous persons." Clearly the minister has doubts that Frank, whom he has often visited, is "very heinous." In fact, he seems to detect in the young prisoner a certain contemporary valor. "Nobody's going to sing Homeric chants about most of the bravery in today's world," the minister says, "is Frank religious? He might not want me to say so, but he is, in the best sense of the word."

In jail, right much though he longs to be elsewhere, Frank quotes a Japanese haiku: "My storehouse having burnt down, nothing obscures my view of the bright moon."

"See," he says, "I love life. I love the world. Everything about it fascinates me. I'm stoned all the time on nothing, just on being alive. The food here is a gastronomical disaster, sure, and I miss a lot of things, but I have to try to learn something from the experience.

Frank's attorney has filed an appeal to the Virginia State Supreme Court. Frank sits waiting and doing calisthenics in the Danville city jail, pallid as your belly from having been outdoors only three days since last February 24, but, he says, "incurably hopeful."

|

![]()